Zero Dose No More

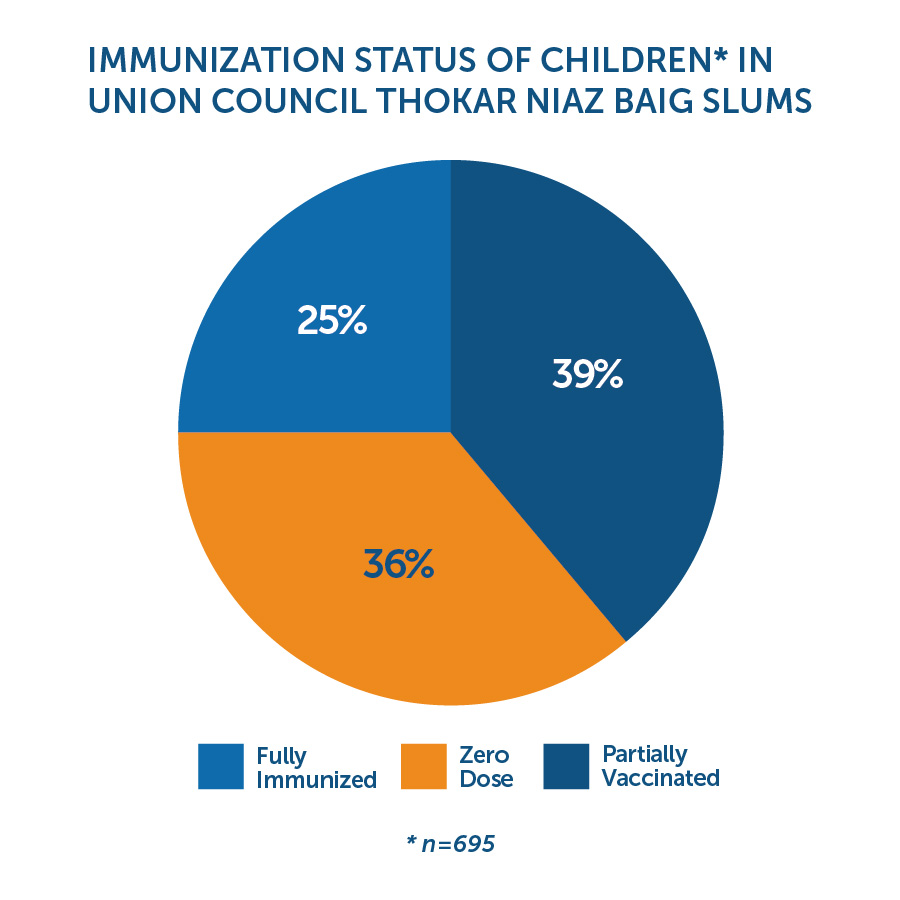

At the heart of Lahore, a city of 11 million people, lies the Union Council Thokar Niaz Baig, an area that is home to just over 70,000 people. Within this enclave is another population of almost ten thousand people, housed in ‘temporary’ shelters that have been in place for decades. This population, often unseen and having access to few health services, is spread across twelve distinct informal settlements. Like millions of others living in similar conditions around the world, the residents of the slums of Union Council Thokar Niaz Baig suffer from the daily indignities of no sanitation, limited housing choices and no designated public health facilities. With illiteracy levels of over 70 percent among mothers, awareness of the need for or benefits of vaccination was almost non-existent. Less than a quarter of the area residents had interacted with a Lady Health Worker, a cadre of community level health workers in Pakistan, and amongst those who had, the prevailing assumption was that their role was to provide information on pregnancy and family planning related matters. Disconnected from services that they didn’t know were theirs by right, mothers in this area did not understand the value of immunization, especially beyond polio. This information gap manifested in over 50 percent of the children under two years of age in the slums being zero dose children – having never received any vaccines at all.

In an already dire situation, the unseen children of Union Council Thokar Niaz Baig slipped all too easily through the net. In 2018, the Civil Society Human and Institutional Development program, better known as CHIP, was tasked with the assessment, identification and vaccination of zero dose children in the slums. CHIP’s team chose to work through various channels to empower mothers. The first step was setting up a Slum Immunization Committee tasked with identifying newborns, defaulters and other missed children through a comprehensive coverage survey. This information brought the reality of the numbers to the District Health Committee. The task was not without difficulties, as Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) raising awareness on hundreds of missed children cast the government health teams in a negative light. Nevertheless, it soon became apparent that what was being offered was a chance for restitution for missed children.

Program Manager Imran Ahmad, who was part of the team which rolled out the initiative, recalls how solving one problem would lead to an awareness of another as once the numbers were in place, a new problem arose – this time on the demand side. Mothers had to be taught about immunization, beyond the more familiar polio vaccinations. Encouraging women to return several times until full immunization was achieved became the focus of work for Community Resource Persons (CRPs). These grassroots immunization advocates were trained on various methods of social mobilization including how to reinforce advocacy messages, alleviate fears around vaccine uptake, issue vaccination cards and maintain eligibility lists. As women from the same community, they were key trusted interlocutors between the committees and the communities they served. Each CRP was assigned 250-300 households and would visit over 50 households each day in a bid to share correct information with caregivers.

Working mothers would be traced to their places of work – whether informal vendors or domestic staff. Area rickshaw drivers were mobilized to provide transport services to the nearest EPI sites outside the slums. No opportunity for influencing change was left untried by Imran and the CRPs. No group that had influence in the slums or over their inhabitants was left out of the community effort. Within months, more than 90 percent of caregivers had engaged in the vaccination program – in essence making sure that no child would be left unseen.

Results of Community-Focused Intensive Approach

Fully immunized children increased from 25% to 86%

Zero dose children reduced from 36% to 4%

Over the “prototype” period of 17 months, this boots-on-the-ground approach bore encouraging fruits. As a result of this community-focused intensive approach, fully immunized children increased from 25 percent to 86 percent, while zero dose children reduced from 36 percent to 4 percent. Caregivers were given a small plastic jacket to keep their children’s vaccination cards by the CRPs and counseled on why it was important to keep it safe and carry it to each visit driving card possession from 4 percent to 95 percent. The approach not only had measurable outputs, it also changed the social narrative around vaccination. Mothers would no longer despair at the onset of fever after administration of Pentavalent 1, and CRPs would be welcomed into people’s homes as they moved around the slums providing information and updates on services, confirming dates for EPI visits and shuttling out of the slum to look for medicine when adverse events would occur.

By mobilizing different cohorts – people, influencers, employers, rickshaw drivers, CRPs – into action, and recognizing that a community is a living organism with different points of influence and power holders, the team was able to convince those who are often forgotten to take up their rights to health and wellbeing and finally to be seen.

Huma Khawar

This Bright Spot story was nominated by Huma Khawar who is a Communications Specialist who supports immunization programmes in Pakistan. She’s a keen advocate of CSO and Government collaboration cognisant of the difference in the power and influence that each partner has. In sharing this story Huma hopes that the role of CSOs will be appreciated in driving positive health outcomes and more partnerships such as the work undertaken by CHIP in Lahore will be recognized and replicated.