Traditional Naming Practices Offer Advantages for Immunization Tracking

In Nigeria’s Yobe State, tradition and modernity find themselves as unusual partners in the quest to secure vaccination coverage to thousands of children. As an administrative area, Yobe has only existed since 1991, when it was carved out from the existing Borno State; but people have inhabited this land from time immemorial moving across the land and establishing customs and traditions that have held families and communities together over centuries. The deeply respected, intricate and rigidly structured emirates that are the traditional government across Yobe’s landscape have presented an unexpected boon to health practitioners in this state.

In 2016, only 7% of children in Yobe had received Penta3 coverage. The numbers were worrying for the immunization advocates who had spent considerable time and resources building up a robust pipeline of vaccine supplies. In seeking to increase coverage, the Yobe State Primary Health Care Management

Board (YSPHCMB) partnered with philanthropic foundations to jointly invest in vaccine supply chain strengthening. Capacity building for healthcare workers and immunization teams had been undertaken, vaccines were available and situated at various service points around the state. In essence, the seeds had been planted but the harvest was wanting.

Turning to the communities to understand why vaccination uptake was stagnant, a few fundamental problems were identified – all the barriers rested within the population the initiatives were set up to serve. General mistrust around vaccination was rampant in many communities, undermining uptake. Meanwhile, outdated data with regards to the number of children to be inoculated meant that the health teams rarely worked with the right information on the number of children below the age of one.

In 2017, YSPHCMB, and its technical partners including the Solina Center for International Development and Research (SCIDaR), began exploring a new approach. Having worked across several states in northern Nigeria, the SCIDaR team was intricately aware of the cultural dynamics that governed the area. The traditional emirates that were the stewards of the region oversaw a system of information influencers who could be useful in turning around the negative connotations that communities had with immunization.Additionally, the SCIDaR team had picked up on learnings from other countries such as Tanzania that were using entrenched traditions as a way to humanize identification of immunization targets. Community naming systems, in particular, had offered up interesting insights on how immunization could be extended through existing cultural practice. Lastly, understanding that the challenge was a demand problem provided insight for where adaptation could provide a solution.

With these insights, the teams began a nuanced process of engagement across the governance structure. Putting their heads together, the health care board and its technical partners, sought a middle ground that would be useful in generating demand.

Yobe Traditional Governance and Support Structure

Emir

District Heads

Village Heads

Community, Traditional, Religious or Settlement Leaders

Resource persons: TBA’s, barbers and market women

Within an age-old tradition a potential answer surfaced.

Traditionally, settlement heads or Mai Unguwas would act as the community census custodian – keepers of the oral roster of births and deaths. This invaluable information went beyond administrative census data which provides numbers but not lineage. The leaders however could provide details leading to the detection of newborns and young children, in essence identifying each child by name and household.

Confronting Challenges

Monetary demand by traditional leaders for their role in the immunization program, which had been a normal offering in polio campaigns

The approach required the buy-in of all members of the traditional structure across the hierarchy from the Emirs, the District Heads, the Village heads and the Mai Unguwas (Settlement heads). A challenge that the team encountered was a legacy of the polio vaccination program, which provided monetary incentives to leaders who took part in the campaigns. The new initiative wasn’t designed to provide similar incentives and the teams had to find creative ways of engaging the leaders who were used to the benchmark set by the polio program. Among these was recognizing the leaders as health champions which encouraged other programs to work through the traditional leaders.

Suleiman receiving the YSPHCMB CE team during an advocacy visit

Leaders from high performing villages or settlements were awarded in an annual recognition ceremony, some of which were graced by the Emir. Concurrently, the health facility representatives would provide regular updates to the village heads about which settlements were not providing information. They, in turn, would use their influence to ensure compliance.

The collaboratively developed approach led to a new practice building on an existing norm. Additionally, the leaders worked with community resource persons such as traditional birth attendants, barbers, market women and others to talk to parents about immunization and help them understand the value it offered to their families and especially their young children.

Results

2016

2019

Rise in Penta3 Coverage

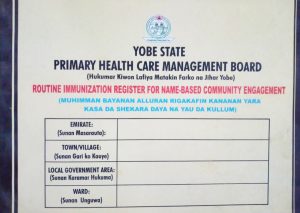

Through this initiative the settlement leaders became the custodians of their community immunization registration ledgers – responsible for maintaining the line listing of each child. These registers became the baseline companion document for the health facility immunization registers and the tool used to identify and track all newborns and babies that had never been registered in addition to those who had defaulted.

The effect of this collaborative effort, which was designed on top of a strong supply chain system, brought about a remarkable change for Yobe. By 2019 Penta 3 coverage had risen to over 50%. But the journey wasn’t without its complications. As the approach began to gain traction, some traditional leaders who had taken part in polio campaigns requested financial compensation for their role in the immunization program as had been customary in the polio campaigns. In some areas, it caused some friction which had to be smoothed over by the Emirs, in other areas, program personnel had to design new forms of valued incentives to offer the settlement heads in return for their participation in the polio vaccination campaigns.

While the move towards contemporary living often means shedding off vestiges of the past, this program has shown that recognizing and valuing tradition and its role in a given context may sometimes hold the key to unlocking the future.

Immunization Insights

Use the familiar: Building a strategy on an already existing norm ensured quick adoption. The learning curve was significantly reduced by using existing practices. Where leaders were not literate, scribes were brought in to help ensure accurate data capture on the community register.

Secure Buy In From the Top: Implementation of the new approach was not met with enthusiasm by all leaders. Having the Emirs as the champions of the program played an important part in ensuring compliance which they took on as their responsibility as opposed to the duty of the program staff. In addition, this approach meant that the naming strategy using community registers became sustainable because it was driven within an entrenched community system that outlived the program investment.

Collaboration and Co-creation: This initiative was the brainchild of several players from within and without the health system. Given the expectation that the program would be executed by these myriad players, the fact that it was an approach that they had all built together meant that the ownership was both clear and complete.

Itoro Ata and Ayotemide Akin-Onitolo

This Bright Spot story was nominated by Itoro Ata and Ayotemide Akin-Onitolo, Managers with Solina Center for International Development and Research (SCIDaR) in Nigeria. They shared this story with Bright Spots to highlight the importance of planning for relevant demand strategies when supply side goals have been met. Immunization coverage needs both sides of the coin activated for targets to be reached.