Influencing Immunization Beliefs – Who Holds the Key?

The results of a national mixed methods study conducted in Nigeria in 2016 brought to light shocking results with regards to immunization coverage. Over four million children were not fully immunized and more than 40% of under five deaths were as a result of Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPDs). The disturbing data raised deep concern, prompting the establishment in July 2017 of a National Emergency Routine Immunization Coordination Center (NERICC), that was represented by similar structures at the state and local government area (LGA) levels. The centers were tasked with driving turnaround in the 18 states with the lowest coverage

rates in the country.

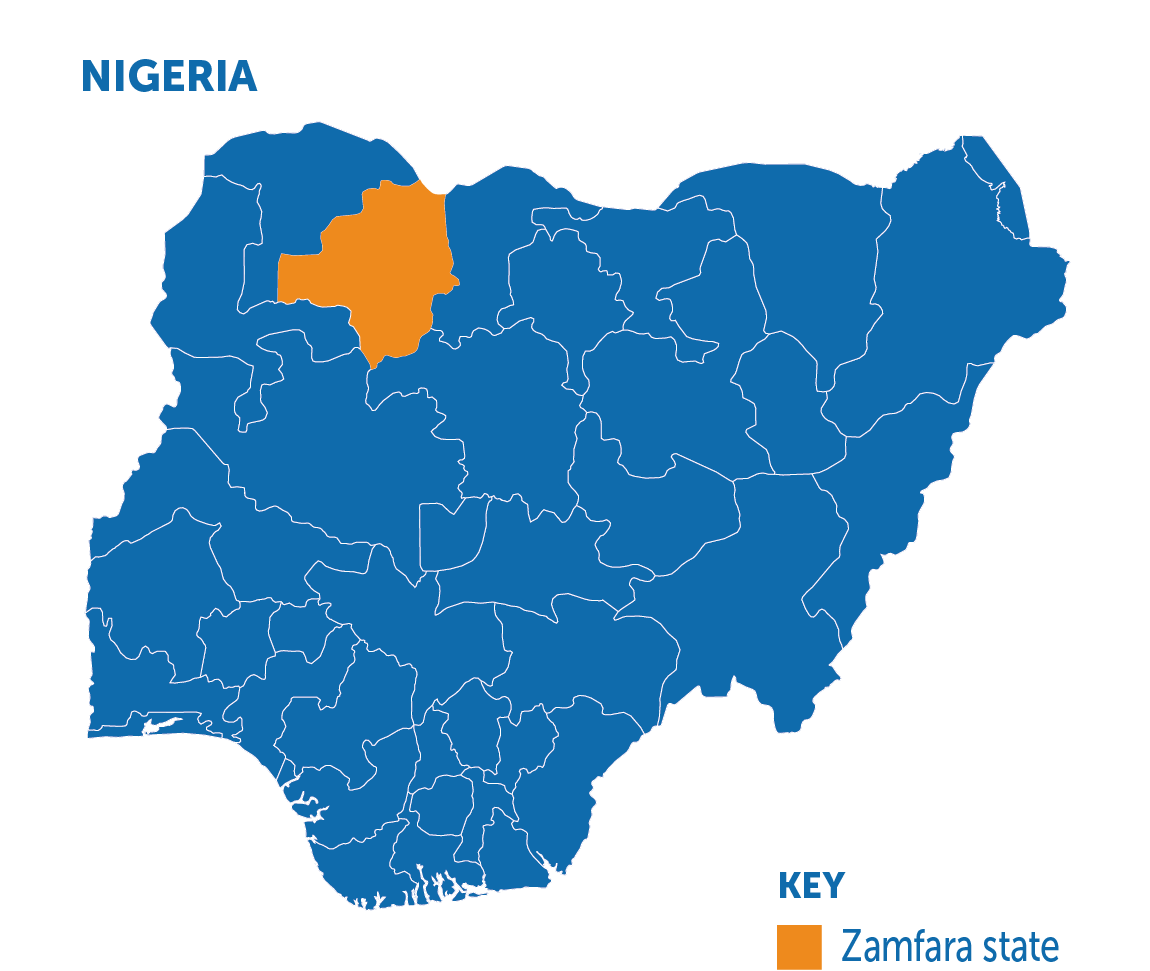

Included in this cohort, was Zamfara state in northwestern Nigeria, where less than 9% of children had been immunized up to Penta3 level. On account of its low coverage, it received early support to establish State and LGA Emergency Routine Immunization Coordination Centers (SERICCs/LERICCs). For the team in Zamfara, the key was trying to understand what was driving vaccine hesitancy and non-compliance. Dr. Attahir Abubakar was a Technical Assistant for SERICC in Zamfara, while his counterpart, Almustapha Alinkilo, served as a Program Manager. Together with other team members, the pair began to interrogate the root causes undermining compliance in the state. It soon became clear that while they sat within a structure in the Ministry of Health that was tasked with improving coverage, the allies needed to drive that agenda were outside of the system.

Nigeria is a deeply religious country, with adherents to both Christianity and Islam. In the northern states, such as Zamfara, Islam is predominant. Across the faiths, adherents rely deeply on the directions of their religious leaders and if there was any conflict with a government directive or program then the word of the local Imam or Pastor, would prevail. Layered onto this was a political structure of leadership and a traditional one – represented at village level by Village Heads and in settlements by the ward heads known as Mai Unguwas. The immunization teams soon realized that the success or failure of any program that pushed vaccinations lay in the buy-in of these leaders and the subsequent messages that they would put out.

The challenge though was that some religious leaders had advocated against vaccination, labelling it as anti-faith. This position was accelerated by prevailing myths around the use of vaccines as a western tool for population control. Attahir and Almustpaha came to understand that it was a battle of beliefs and the only way to turn the tide lay in confronting and changing existing convictions. So began the painstaking process of mapping and personally engaging with the religious leaders at grassroots level across the state. Conversations were steeped in respect, the technocrats acknowledging the roles, responsibilities and influence of the leaders. The team would then introduce the concept of immunization from the basis of their shared faith, such as highlighting how on arrival for Hajj in Jeddah, all pilgrims would receive two polio drops or the examples from the Quran where the Prophet would instruct followers on the principles of quarantine. The discussions were not always smooth, with some clerics showing a reluctance to go back on earlier pronouncements against vaccines.

Slowly but surely through concerted engagement, which was backed by colleagues from the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the Council of Ulama and Ministry of Local Government Affairs, the tide began to change, and a new vaccine narrative started to take root in the homes and villages in Zamfara – that it was the responsibility of all caregivers, whether grandmothers, fathers or mothers – to ensure that their children were vaccinated. The same message was repeated by the Mai Unguwas, who would also be responsible for keeping one portion of the vaccination card of the children in their settlement and following up defaulters, in essence making them custodians of the community’s drive towards wellness. Caregivers would be reminded how polio vaccinations had wiped out the disease, yet children were still dying from yellow fever and measles which could be avoided if full immunization were reached. Highlighting the opportunity cost of a breadwinner having to take care of a sick child in terms of money and days lost to farming was another argument that was used to elaborate the price of not being vaccinated by local leaders.

With multiple sources of influence – religious leaders in mosques and village leaders in community meetings – reporting the same message, slowly a change began to take hold. Attahir shares, “Leveraging the influence that religious leaders have in their communities has been central to the change in Zamfara state. Thousands of people would not have been reached through other means, and even if they had been reached with a health message, the leaders were the only ones who had the power to sanction a new belief.” With new health threats emerging each day, understanding who holds the key to the gate of wellness is truly critical for success.

Attahir Abubakar

This Bright Spot story was nominated by Attahir Abubakar who is as a Technical Assistant with Zamfara State Emergency Routine Immunization Coordination Center in Nigeria. As a technical specialist in immunization, Attahir wanted to share this story to encourage other practitioners to look beyond health actors and health structures to sector-external allies who can be instrumental in driving immunization goals. His experience over the past few years in Zamfara has confirmed that goals are reached only through collaboration and through understanding the culture of those who are being served.