Digitized Supply Chain Delivers Vaccines to the Last Mile

With a population of over 1.3 billion people, India is the second most populated country in the world with close to 27 million births each year. India produces most of its own vaccines, and its vaccine supply chain supports one of the largest immunization programs in the world. It is a massive undertaking: the government procures and distributes 600 million vaccine doses across 27,000 health centers every year, reaching 156 million people annually.

For decades, getting vaccines to every eligible child and woman, on time and in good condition, was an immense logistical challenge, what with the huge population, the vastness of the country and its diverse terrain, combined with constraints of infrastructure, weak management information systems and inadequate human resources. The vaccine supply chain was further hampered by the fact that program managers at all levels did not have real-time visibility of stock supplies and storage temperature of the vaccines in the health centers. And so, despite adequate vaccine supply in the pipeline from national to state level, instances of stockouts, overstocking and wastage at lower levels were quite common. As a result of poor information flow, it took an average five days for stocks to be replenished at immunization sites, and children and women would often be turned away due to unavailability of vaccines.

The introduction of the revolutionary Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network (eVIN), an integrated electronic vaccine supply chain and management system, changed all that, transforming India’s vaccine cold chain into an efficient, well-oiled system that reaches children and women in every part of the country with appropriate amounts of quality vaccines whenever they are needed. eVIN was launched by the Government of India in 2015, supported by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which has supported India’s immunization program since 2002. As is the case with many other countries, India has begun transitioning away from Gavi support. The country is expected to begin fully self-financing all aspects of its vaccination programs by 2021 and so establishment of the new system greatly enhances the country’s preparedness for the transition.

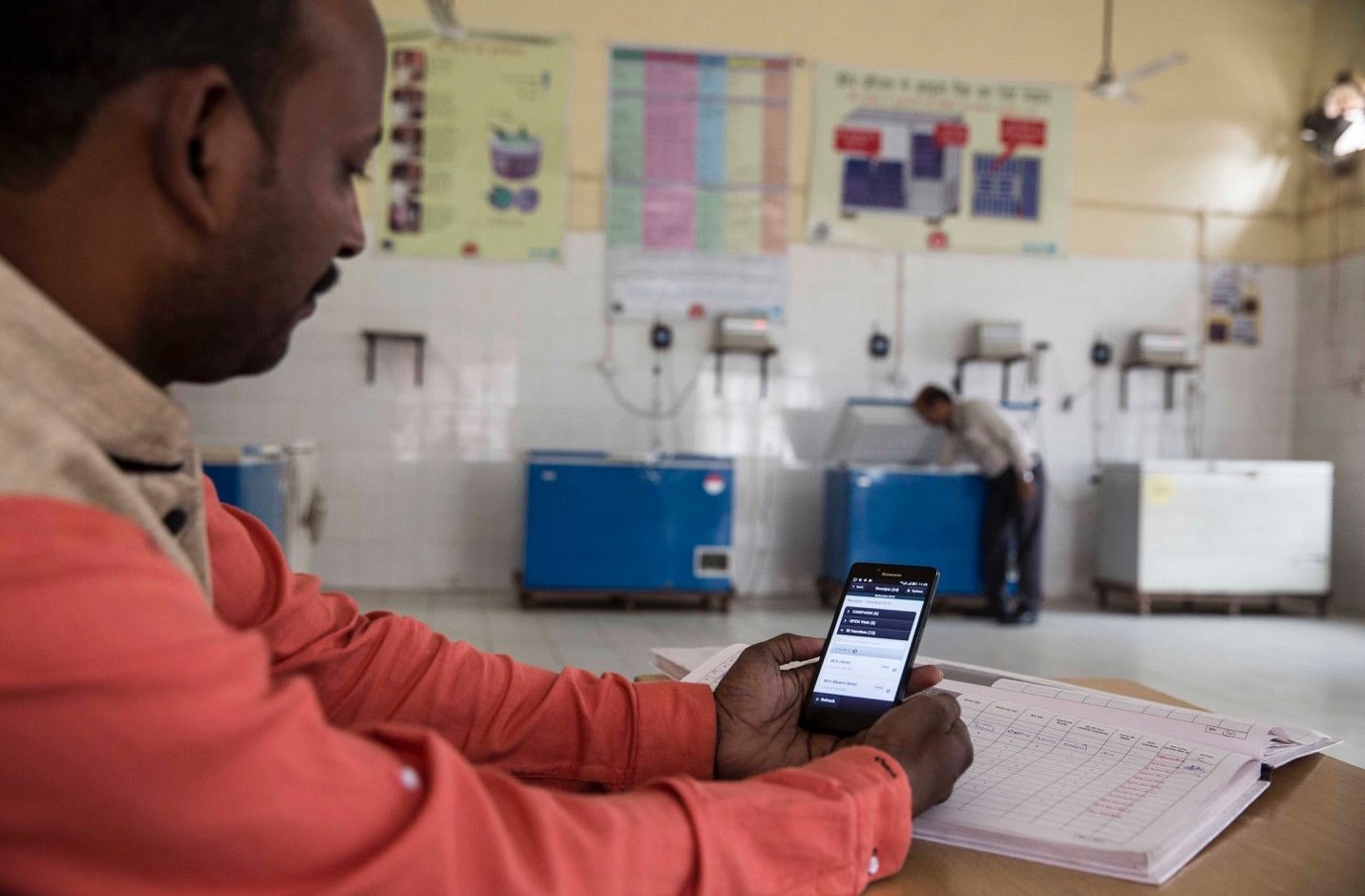

eVIN digitizes vaccine stock data and monitors the temperature of the cold chain at all levels through a smartphone application. The data is stored in a state-of-the-art cloud server supported by high-end analytics, enabling real-time monitoring through online dashboards. The technology is customized to work efficiently in India’s low-resource network settings, manned by a well-trained network of human resources in every district that ensures timely entry of quality data and effective, informed decision-making.

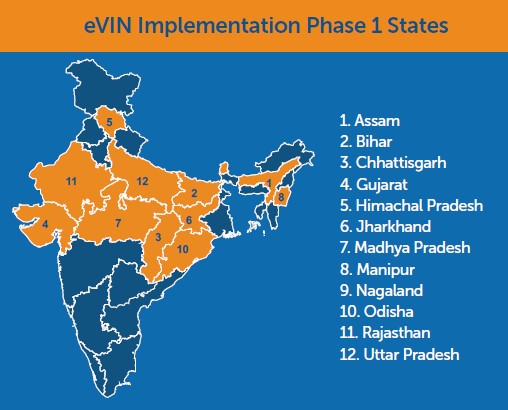

The electronic system was first piloted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) in 2013 in two districts and scaled up in 2014. The Ministry decided to include the set-up and management of eVIN as an additional activity in a health systems strengthening proposal to Gavi and to ask the UNDP to run it. Until then, two other UN agencies, UNICEF and WHO, had been recipients of the Gavi grant with a focus on communication, transitioning the polio program to routine immunization and cold chain equipment management. On the Government’s request, UNDP developed a proposal that was submitted together with those of UNICEF and WHO in a consolidated health systems strengthening application, to improve accountability in the supply chain management. The result was the design and development of eVIN in 12 states of the country: Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Manipur, Nagaland, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh.

At about the same time, India was in the process of revising the country’s Comprehensive Immunization Strategic Plan (2013-2017). Three significant gaps were identified in the vaccine supply chain. First, the vaccines were procured centrally by the Government at national level and distributed to the states through a centralized pipeline, but there was little visibility of where manufacturers’ stocks went once they left managerial oversight from the central level. Secondly, the situation was aggravated by the weak, manual record-keeping system in use at the time. It was clear that a new approach with a more reliable system was required. And thirdly, a study by the Ministry had shown that with adequate human resources, appropriate technology and support, it was possible to reduce vaccine stock-outs and improve stock availability across India.

Implementation of the first phase of the project began with a team of around 180 from the three larger states of India – Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. While the pilot by the MoHFW in Bareilly and Shahjahanpur districts of Uttar Pradesh used very simple software that was only accessible on basic phones, the next part of the first phase used an upgraded version on a smartphone across 12 states. Along the way, insights gained from the field, feedback from the Departments of Health and Family Welfare in the states and discussions with the UNDP, technology engineers and other partners had resulted in multiple iterations of the software targeted at increasing supply chain efficiency.

Source: UNDP India

Working with India-based supply chain software experts at Logistimo, standard operating procedures (SOPs) were updated to remove barriers to the smooth functioning of the vaccine value chain. Barriers included information-sharing roadblocks which only allowed districts to transfer vaccines downstream to their health facilities, but not laterally to another district without authorizations and signatures. With the new system, an e-alert was generated whenever supplies need to be moved horizontally enabling load balancing and effective stock management where a district immunization officer could give the approval online. In addition, vaccine requisitions were generated automatically and buffer stock was seamlessly managed in line with the SOPs.

Temperature loggers were installed across the supply chain to safeguard the quality of vaccines. These were continuously and remotely monitored in each piece of equipment storing vaccines. Any temperature breach would automatically trigger an alert to the cold chain handler who would make the necessary adjustments to keep the vaccines safe.

TRAINING TROOPS FOR TECHNOLOGY

The Gavi grant was designed as a catalytic instrument for health systems strengthening and long-term sustainability of routine immunization in India, with the Government committing from the very beginning to scale up the program and to work towards funding it fully. It was a massive undertaking, and the right teams were a critical element for success. The first phase covered approximately 13,000 cold chain points, with two people trained per point. Training was not isolated, but went hand-in-hand with mentorship.

National Organization Structure

Lead Team

Based in New Delhi. Charged with coordination, management, technical support and software development.

State Level Teams

These are headed by senior project officers and were created to support districts.

Regional Level Teams

These are comprised of project officers and public health experts. Each district is supported by one vaccine and cold chain manager.

State teams were created to support districts: each district was supported exclusively by one vaccine and cold chain manager, whose role was to ensure that training, follow-up and mentorship of the cold chain handlers was done, that they were entering data on time, and conducting digital and physical checks to ensure that the vaccine stocks were moving, thus ruling out discrepancies between actual stock and data entered into the app. Teams of project officers, all public health experts, were based at regional level, while state level teams were headed by senior project officers. In addition, there was a support team of 12 IT officers and a lead team of 10 in New Delhi charged with coordination, management, technical support and software development.

Training was elaborate and intense. A team of master trainers at national level focused on understanding the system and the immunization program, and then conducted state level training. Standardized training materials and protocols were developed for use in all the states. First to be trained were UNDP sta – vaccine supply chain managers, project officers and senior project officers. The four-day course included everything from manual data entry to the smart-phone application, after which it was the UNDP team’s role to train Government officials, beginning with state and regional vaccine store managers, then onto the districts.

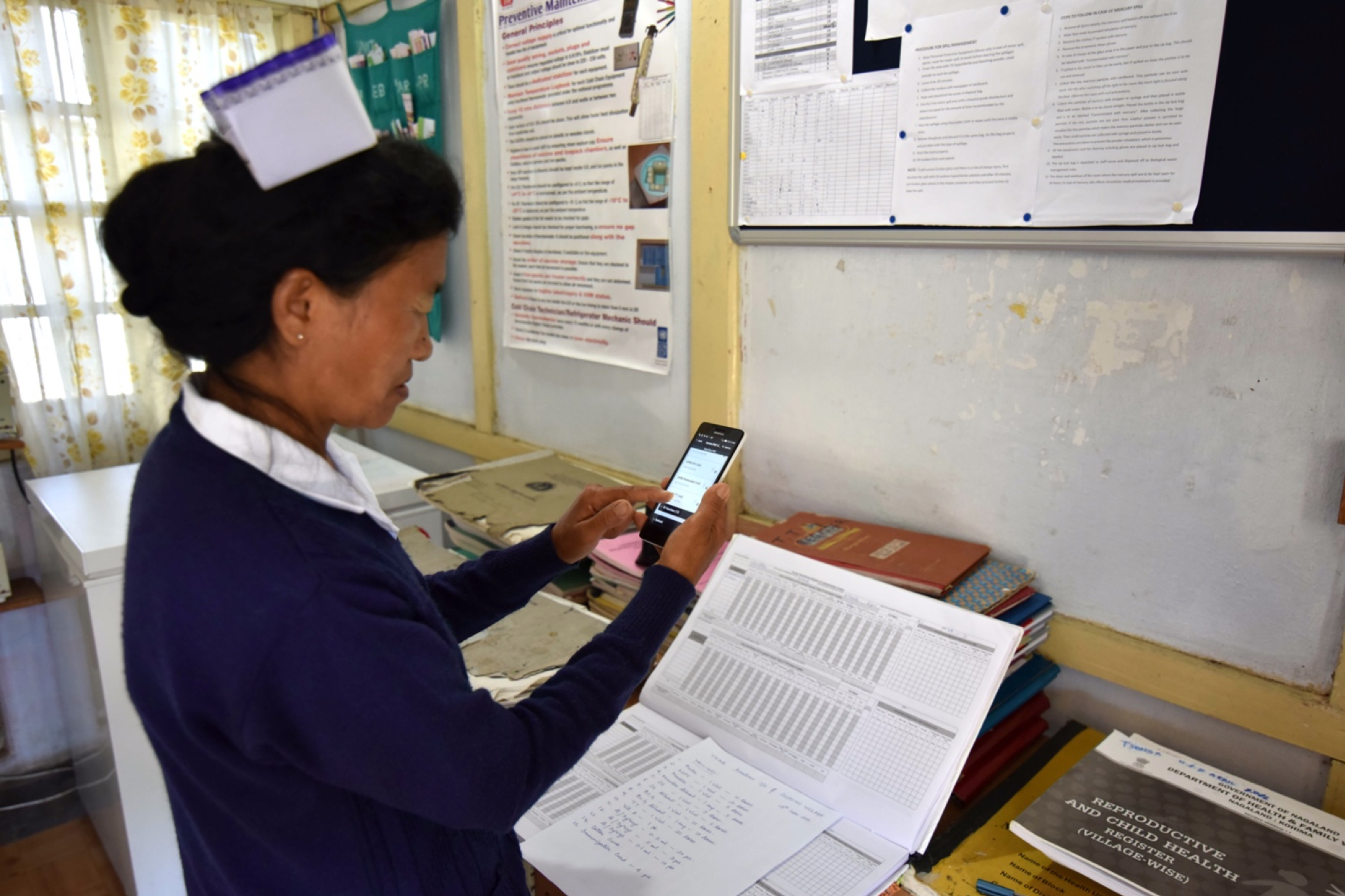

While the state and regional training sessions went relatively smoothly, a human resource challenge arose at the district level. In its first phase, the project covered 370 districts, with populations ranging from 100,000 to 9.5 million people, and with 50 to 100 cold chain points each. Most of these cold chain handlers were nurses or midwives, 60% of whom had basic education, and most of whom had never held a smartphone before. Moreover, they were not full-time vaccine managers; it was an additional task assigned them as they distributed vaccines to immunization session sites. The logistics of getting each and every one of these cold chain handlers to the district headquarters for training posed quite a challenge, but it was critical that everyone be on board, and ultimately a government logistics team ensured 100% attendance.

After the training, emphasis was placed on mentorship and close monitoring by supply chain managers at district level to ensure correct data entry, provide support for technological issues and address any supply chain issues, such as route planning. While calibrated for size and population, an average of a hundred vaccine chain handlers and managers were trained in every district. With smart phones and on-call support and mentorship, adoption of the system was quite smooth. The activity rate has remained high, with over 24,000 health facilities covered and over 99% data entry – which reflects the comfort level of the cold chain handlers in understanding and adapting to the technology. At present, data entry is completed by the Government staff, as is all the training, with UNDP only providing technical back-up support where necessary. Five years after the initiative was launched nationally, post-training follow-up and mentorship by UNDP continue, as well as regular refresher training to keep up with software updates every four to six months.

While technology has played a major role in getting the country’s immunization system to where it is today, the success of eVIN hinges equally on three Ps – the product, the people and the process. So well-integrated is the system that the human resource network cannot function independently of the software or vice-versa. It has, in eect, evolved into a big data architecture, based on a cloud-based platform that allows a great deal of automation of the system, with features that facilitate efficient vaccine supply management such as predictive, consumption-based flow-casting.

MINISTRY AT THE HELM

The fact that India’s vaccine system was anchored on a centralized government program proved essential for the relatively smooth roll out of eVIN to the states. Vaccine distribution, supply and requisitioning, for instance, were already standardized. Leveraging the established uniform protocol of implementation, the Ministry of Health sent letters to states introducing the system and how it would be implemented with the support of the UNDP. This move by the Central Government greatly facilitated initial buy-in by the governments of the three pilot states – Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

Nevertheless, there were unique hurdles encountered in various states as the program was implemented. In states like Nagaland in the north-east part of India, for example, the mountainous terrain made travel for training a difficult task. Some states took longer than others to approve implementation modalities due to internal control processes, while others had less developed cold chain infrastructure. Rajasthan, for instance, had a cold chain point every five kilometers while those in the vast, hilly regions in the North Eastern states of Nagaland and Manipur were more sparsely located. Topography and climate were a cause of concern in states such as Himachal Padesh and Arunachal Pradesh with regards to transportation and preservation of vaccines. Then there was the need to translate communication and training material to regional languages for use by the cold chain handlers.

Smartphones: A Twin Win From Morale and Data

Being given handsets with internet access and the training on how to use them was empowering for the last mile cold chain handlers. It not only gave them a great sense of pride in their work but also an increased sense of ownership of the eVIN system, which has ultimately translated into greater immunization coverage.

Smartphone handsets are given out to the vaccine cold chain handlers at the end of the training program as their facilities go live on the eVIN system. Entered into the government asset inventory with proper asset transfer protocols, it then becomes the responsibility of the facilities to replace any missing handsets. It is notable that, while over 300,000 handsets have been transferred to the facilities in the last five years, less than 5% have actually been lost or broken, indicating ownership not just of the phones by the last mile workers, but also of the program.

MINIMAL ERRORS, GREATER SCOPE

The digitization of the supply chain system has had a profound effect on both the quality and quantity of data generated. Previously, paper forms were manually filled at the session site level then sent up to the sub-district level, where the information was collated before being sent to district and then state level. The process often resulted in a significant degree of data errors or manipulation. Not so with eVIN, because once information is keyed into the smart phone, it is stored in the cloud, minimizing the possibility of error or manipulation before it is analyzed by program managers.

Notably too, while information was originally collected at cold chain point level, going forward, it will also be captured at session site level, enabling project managers to identify which planned activities had been undertaken, achievements versus set targets and actual levels of vaccine usage and wastage. Unlike many countries which use a permitted level of wastage advised by WHO or UNICEF to gauge the efficiency of their immunization programs, eVIN has enabled India to generate its own data to accurately determine the amount of vaccines needed for every immunization site, greatly reducing wastage and optimizing the system. This move will help track vaccine consumption till the last mile, which will entail training of around 250,000 auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANMs) on the system. This has the potential to generate ten times more information on numbers of children immunized and doses consumed.

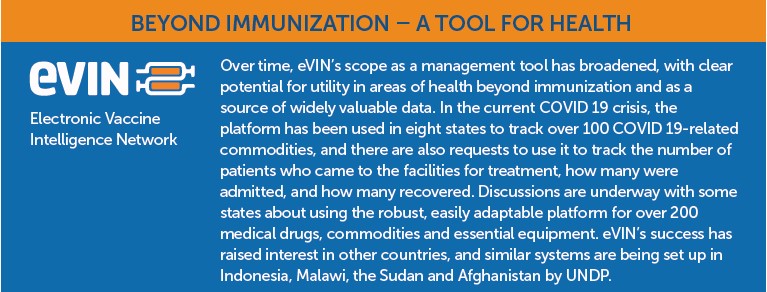

Presently, over 4.5 million transactions and 80 million temperature samples are captured on eVIN every month. The system generates analytics from 20 major indicators to inform evidence-based decision-making and accountability. While the stockout rate of vaccines has gone down by nearly 80%, the time taken to replenish stocks has also reduced from five to two days on average. An independent techno-economic assessment of eVIN reflects a 25% reduction in wastage of any vaccine for reasons such as non-usable vaccine vial monitors, freezing, expiry or breakage of vials. It is estimated that for every rupee invested, eVIN yields a return of three rupees.

THE LEARNING HARVEST

The implementation and scale-up of eVIN in India generated valuable lessons that could be adapted in other countries and other areas of health. Many of those lessons were used to improve the system through co-creation with partners. From the beginning, the thorough region-by-region assessment in preparation for scale-up of eVIN greatly helped to streamline India’s immunization system, ridding it of non-functional elements, filling up infrastructure gaps and setting up cold chain points where needed.

“The design of the whole programme worked quite well; we kept evolving as we went ahead, based on feedback from all stakeholders, especially from the ground. What maybe we could do better was to factor in various aspects of coordination with the state governments from the beginning for a smoother transition and scale up. We are doing this for the states we are implementing in, now, in the second phase.” observes Dr Manish Pant, head of UNDP India’s Health and Governance Unit.

“The design of the whole programme worked quite well; we kept evolving as we went ahead, based on feedback from all stakeholders, especially from the ground. What maybe we could do better was to factor in various aspects of coordination with the state governments from the beginning for a smoother transition and scale up. We are doing this for the states we are implementing in, now, in the second phase.” observes Dr Manish Pant, head of UNDP India’s Health and Governance Unit.

A major learning from the implementation was the importance of empowering the last mile worker when strengthening any health system because systems are as good as the people who run them. Without them, nothing works. Another key requisite for successful implementation of programs to strengthen public health systems is government buy-in, especially in a federal country like India where there are many different bureaucracies, underlining the need to build a common shared understanding of what success looks like. Shared belief builds shared ownership. In the case of eVIN, this was achieved through high-level advocacy with the Central Government and allowing it to champion the product with state governments. The acceptance was then boosted by peer-to-peer transfer of interest among states, enabling the system to grow and scale up organically.

An important lesson in digitizing health programs was that the initiative should drive the technology, rather than the other way round. Designing a digital health project should never be so disruptive, for instance, that existing SOPs are completely by-passed, as this would require building a new culture, an investment that would be extremely difficult to do in a health system. Instead, digitizing key elements of the system that impact service delivery without disrupting the way providers do their work, and simply updating what they already do from manual to digital is a more prudent approach.

Additionally, the role of data in informing programmatic direction cannot be overemphasized. As the link between the data generated and improvement in services becomes more evident, acceptability and ownership of the system grows.

Over the years, eVIN has evolved significantly as operational lessons are learnt and applied along the way. Improvements have been made in logistical planning for training sessions; delivery of training; engaging government counterparts; program presentation; the call center and the back-end support system.

In the end, the implementation and scale-up of eVIN provides a solid platform for India to achieve its goal of efficient and timely supply of vaccines, until every last mile is reached.

Voice from the Field

“My name is Anjana and I work in the state of Karnataka in South India, as a senior project manager heading the state team. My experience with eVIN is that it has brought a holistic approach to immunization, including digitizing vaccine stocks, clarifying standard operating procedures, and providing clear, uniform documentation across all states of stocks received and dispatched.

Our cold chain handlers are now very well versed in supply chain principles. They know how to issue vaccines to the immunization stations using the “first expiry, first out” rule to avoid ending up with expired vaccines. This ultimately reduces wastage and makes eVIN a very cost effective program.

The program has also been a great avenue for empowerment of our cold chain handlers, many of whom are women who had never used smart phones before, but who are now confidently using the technology to facilitate distribution of vaccines and to collect data for reports to the districts. The data has proved very useful for tracking down vaccine batches whenever there is an adverse episode during an immunization field event.

Based on data received from the field and passed through district level to the state level, we at state level are able to determine net allocation and usage of vaccines, allowing us to project allocation of vaccines to ensure that every child gets the vaccines they are due for. Using dashboards and various other kind of reports generated by eVIN has really helped the state and district authorities to make informed decisions on strengthening and streamlining the vaccine supply chain. Being able to monitor the vaccines means we can use them well before they expire, so ultimately there is an enormous amount of reduction in vaccine wastage, there are fewer stock-outs and a lot of cost-saving has happened.

Thanks to UNDP, we have a strong human resource component at all levels – state, regional and district – who constantly monitor and manage these vaccine supply chains, supporting the government and making it all work very efficiently.”

Sugandha Nagar

This Bright Spot story was nominated by Sugandha Nagar, a development communication specialist who leads communication for the health and governance initiatives at the United Nations Development Programme in India. Sugandha has managed various communication components for the Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network (eVIN) over the past four years. Previously she served with various non-governmental organisations and government departments in India, driving behaviour change communication and more. A graduate in English Literature from the University of Delhi, Sugandha holds an MA in Mass Communication and another MA in Sociology from the Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi.