Demonstrating the Power of PEI/EPI Synergies

As one of only two polio endemic countries in the world, Pakistan’s work around polio eradication is a major focus of the country’s vaccination efforts. Yet, even as the push towards the elimination of polio continues, the importance of routine immunization (RI) in Pakistan to prevent other vaccine preventable diseases (VPD) cannot be overstated.

In the southwestern region of the country lies Sindh province, one of the country’s four administrative areas. Sindh is a province of contrasts. While it hosts the country’s commercial hub, Karachi, a large proportion of its population still resides in rural villages that dot its desert terrain in the West, the lush Indus Valley, and the floating communities that live offshore in the warm waters of the Arabian Sea. Karachi also hosts large urban slum populations that are difficult to reach with health services, including immunization, on a consistent basis. These contrasts make a single approach to increasing immunization coverage inconceivable and highlight the need for differentiated approaches in different parts of the province to achieve success.

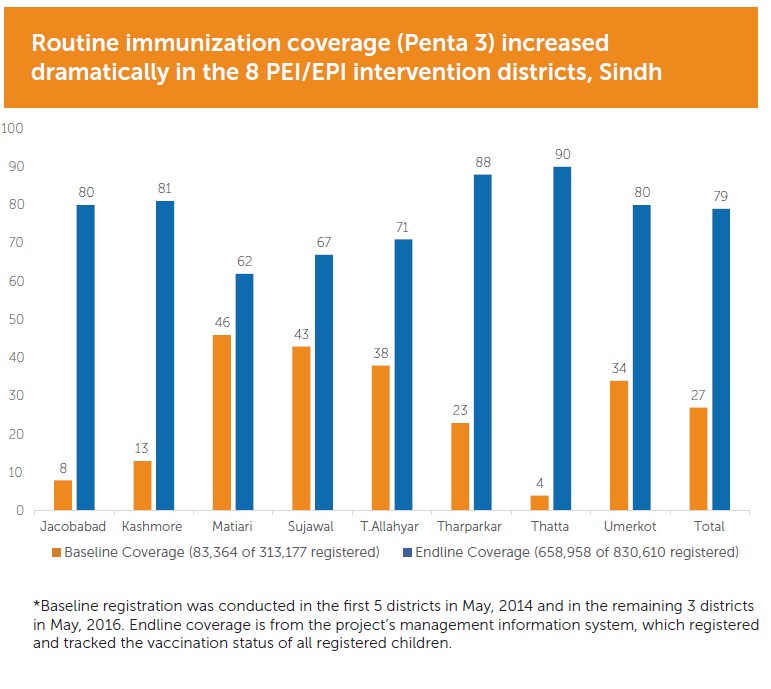

By 2013, the need for a new approach was clear. According to the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (2012/13), Sindh had a fully immunized child (FIC) coverage rate of just over 29% overall and less than 14% in its rural areas. Globally, the RI indicator is completion of three doses of Pentavalent vaccine which protects against DPT, Hep B and Hib, and is known as Penta 3. As shown below, Penta 3 coverage was slightly better than FIC in Sindh, but still extremely low. With continuing polio outbreaks and measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases on the rise across Sindh, all agreed that there was an urgent need to turn the RI situation around.

| SINDH PROVINCE ROUTINE IMMUNIZATION BASELINE 2013 (Source: Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, 2012-2013) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| % OF CHILDREN WITH ALL BASICS VACCINATIONS AT 1223 MONTHS OF AGE | % OF CHILDREN WITH PENTA3 VACCINATION AT 1223 MONTHS OF AGE | CHILDREN WHO HAVE RECEIVED NO VACCINATIONS AT 1223 MONTHS OF AGE | |

| SINDH PROVINCE | 29.1% | 38.6 | 8.5% |

| URBAN AREAS | 51.5% | 66.5% | 2.8% |

| RURAL AREAS | 13.7% | 19.5% | 12.4% |

In 2016, a new mother and child initiative took root in 16 out of 29 districts in Sindh. While the focus was advancing maternal and child health indicators, building new approaches to comprehensive immunization was at the heart of the initiative being driven by the Government of Sindh’s Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI), with technical support from John Snow, Inc. Eight out of the sixteen project districts were identified as high priority RI areas and offered a testing ground for new action.

As in many countries, ensuring efficiency in health interventions was a continuing quest in Pakistan. With thousands of health actors already involved in frequent polio vaccination campaigns (monthly in many cases), the raw numbers seemed to indicate sufficient personnel for immunization. However, while the personnel numbers suggested a suitable human resource investment was in place, the low routine immunization coverage told another story.

The answer to the conundrum was more complicated than anticipated.

For many years, immunization advocates had championed the idea of offering all routine EPI vaccines during polio, measles and other campaigns. On the face of it, this opportunity for synergy seemed obvious, but despite years of discussions and proclamations, the approach was still stuck at the suggestion stage.

Three Main Barriers to this Programmatic Shift

Timing constraints

Human resources being deployed to other work

Goal achievement

Three main barriers to this programmatic shift were identified in Pakistan: lack of time, human resource constraints, and the country’s urgent need to achieve its polio eradication goal. Lack of time: Polio campaigns in the province typically took between 15-20 days per campaign, meaning that the government vaccinators responsible for routine immunization had little time left in the month to plan, conduct outreach and implement non-polio activities. Human Resources: Government vaccinators worked alongside polio vaccination teams that were made up of campaign-specific volunteers from community initiatives and NGOs. Although there were many volunteers and vaccinators, it seemed that there were never enough human resources to dedicate to both polio and routine immunization. Goal achievement: Finally, as one of the last remaining countries in the world with wild poliovirus, Pakistan’s polio eradication goal was still top of mind for the hard-hit country’s officials, and they were understandably anxious that the frequent polio outbreaks, including those in Sindh, not be given a chance to take hold.

Also, hidden within these obvious impediments were less acknowledged ones including: a reluctance of many health managers to change the status quo of the operational rollout of the well-established polio campaigns; the reality that PEI offered better monetary incentives to those working on polio campaigns than the Health Department had the resources to offer for RI activities, thereby unduly incentivizing one program over the other; the inaccessibility of many hard-to-reach villages; and the fact that managers and government vaccinators did not consider themselves replaceable by community volunteers for the polio campaigns.

Eager to move the idea of EPI-PEI synergy from discussion to action, the team methodically assessed opportunities and barriers and designed a framework for the new synergistic approach. Key to rollout was the approval and endorsement of the Provincial Authorities (Minister & Secretary of Health, Polio Emergency Operations Coordinator and Program Director EPI) and of the District Managers (Deputy Commissioner and District Health Officers) who were responsible for deploying vaccinators for different activities.

Despite the go-ahead from the provincial team, endorsements were not easy to secure. Long conversations were required to shift minds and convince DHOs of the potential of the not-so-new idea. Frustratingly, it sometimes seemed like just when a new officer would endorse the plan, they were assigned out of the district and the team was back to square one.

A first group of nine vaccinators was assigned to the initiative, finally allowing the provincial team to test the approach in one district. The first step was conducting a micro-census in each area and laying the groundwork for the second step enrollment of all pregnant women, newborns and children under two years of age. A regional network of NGOs was contracted to conduct both steps, which showed just how many children in the 0-23 month age group the vaccinators had to plan for. Surprisingly, the effort uncovered not only many children that had never received any vaccination, but also hundreds of communities that had never been captured in any previous planning process. Many of these communities were found deep in the vast desert spaces of Western Sindh, but there were similarly missed women, children and communities in all eight districts.

| Number of Children Registered (0-23 Months) at Baseline and End of Project in the 8 Intervention Districts of Sindh | |

|---|---|

| Registered | |

| 2014 | 313,177 |

| 2017 | 830,610 |

The direct result of the micro-census was that all children under two were identified and enrolled into the new expanded RI target group. Leading this effort were local leaders and immunization supporters at village level who were critical in helping identify pregnant women and new mothers and their babies, especially in previously uncaptured villages.

The third step was building detailed vaccination plans with the names and locations of children who had missed or were due for their next vaccinations and could be reached by our small group of vaccinators. Data on births, vaccination records and locations were included for each site. Through this initiative, large groups of unvaccinated and under-vaccinated children were finally reached with all vaccines – pointing to the success of the new approach in serving as many children as possible. Ultimately these three steps provided a critical evidence base for the redeployed teams to plan their operations.

Activities Driving Progress

House-to-house registration (micro-census)

Micro-planning

Outreach based on micro-census

Fuel, oil and lubricant to facilitate vaccinator’s travel

Community mobilization and engagement

Tracking and caregiver reminders

Active monitoring and problem solving

Capacity building

The activities above are implemented under Polio Eradication Initiative and Expanded Program on Immunization synergy (PEI-EPI synergy)

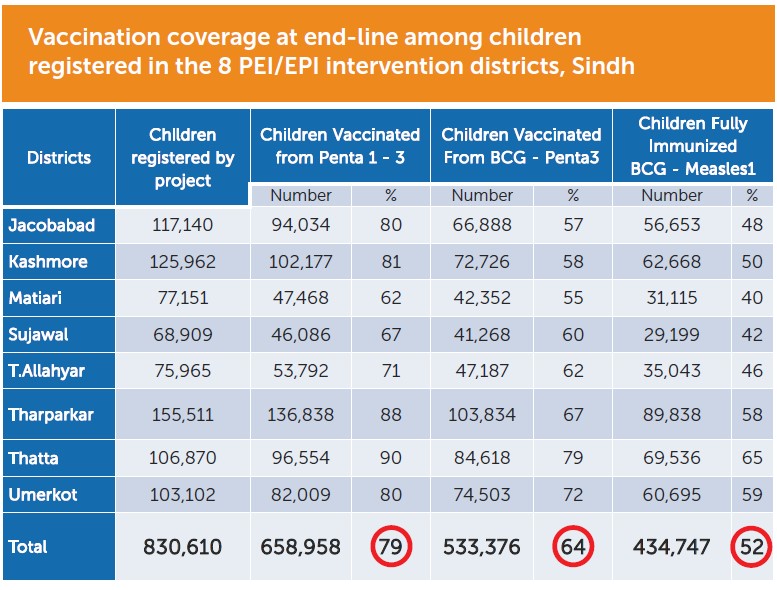

The “simple” idea of synergy was rolled out between 2016 and 2017 and as each district joined the approach, results started rolling in quickly. From the small group of nine, eventually 500 vaccinators were taking part in the initiative during and between the polio campaigns resulting in 16,835 outreach sessions. Many of the children reached were being vaccinated for the very first time. From a dismal low of 27% in 2014, this synergistic approach enabled 658,958 (79%) registered children to receive three doses of Pentavalent + 3 doses each of PCV + OPV_+_IPV by the end of September 2017, in the eight districts of focus in Sindh.

Immunization Coverage by September 2017

658,958 (79%) registered children received 3 doses of Pentavalent + 3 doses each of PCV + OPV + IPV

Outreach Sessions in Synergy Districts

16,835 RI outreach sessions were conducted

Over 300,000 children vaccinated with different RI antigens during campaigns, including OPV and IPV

From May 2016 to September 2017

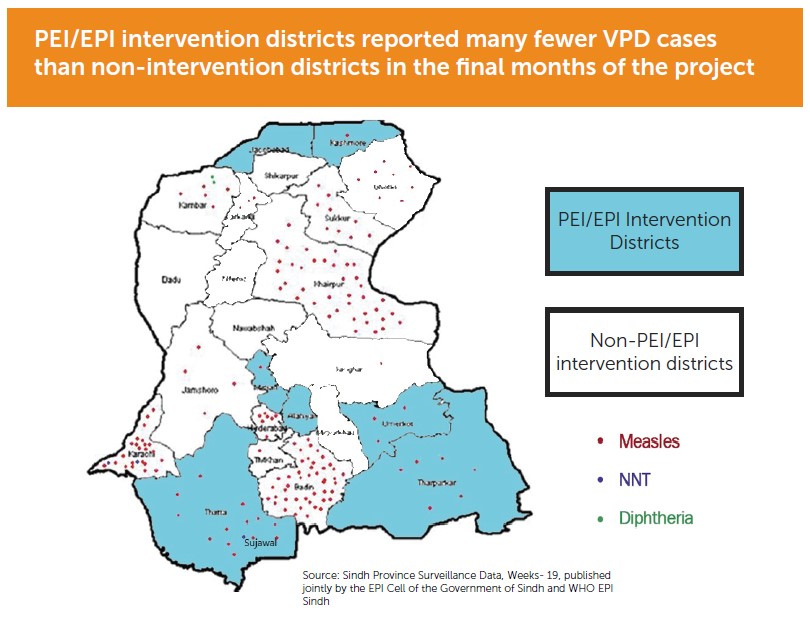

During the same period, polio coverage did not suffer. Conversely, coverage levels across all vaccines increased. Additionally, significantly lower numbers and rates of vaccine preventable diseases were recorded in the 8 intervention districts as compared to other districts in Sindh province. This alternative approach to PEI/EPI synergy had outsized results for RI without negatively impacting and potentially contributing to on-going polio eradication efforts.

Immunization Insights

Target the highest decision maker: Given the high turnover of District Health Managers, the team kept losing valuable time engaging with and introducing each new district staffer to the approach. In retrospect, securing a memorandum of understanding with the provincial head that was binding on any new district staffer would have been a more effective and less time-consuming approach.

Design For Context: A number of vaccinators had not been able to reach families and villages in outlying areas on account of significant transportation costs and difficult terrain. The initiative used motorcycles, four by four vehicles, boats or camel carts as necessary that allowed for quick access to these hard-to-reach areas, making a sizeable difference in the number of families that were identified and served.

The same old approach will give you the same old result: The team encountered a lot of resistance from PEI practitioners intent on reaching their targets and reluctant to give up any resources that may compromise the achievement of those targets. Like many entrenched areas of practice, ceding to innovation or even minimal change was very difficult, even though existing methods hadn’t yet achieved the target of polio eradication. With the new synergistic approach – both RI and polio vaccination coverage went up to the surprise of many.

Dr. Tariq Masood

This Bright Spot story was nominated by Dr. Tariq Masood, an Immunization Manager with JSI in Pakistan. As one of the last polio endemic countries in the world, showing that polio eradication can be an accelerator for routine immunization when a synergistic approach is adopted by all players is a valuable contribution to the immunization community.